Memories: Roald Dahl and ‘ritual cruelty’

As Donald Sturrock reveals in a biography, Roald Dahl’s schooldays were filled with the ritual cruelty of terrible canings. Dahl was a prolific author, famed for a number of children’s stories and short ‘tales of the unexpected.’ We met him here when we looked at his short story Galloping Foxley.

Discipline at Repton was maintained by the senior boys, in particular

prefects known as “boazers”. Each house was, as Dahl put it, “ruled by a boy of

17 or 18, who was the Head of House. He himself had three or four House

Prefects. The House Prefects were the Gods of the House, but the Head of House

was the Almighty.”

Repton boasted an entrenched system of corporal punishment for offences

as minor as forgetting to hang up your football kit in the changing room. In

the 1930s, the cane or the strap were, as Tim Fisher described it, “an

automatic and assumed part of the growing-up process”. They were part of a

culture of toughening children up that would survive in England well into the

1960s. As an adult, Dahl objected profoundly to the culture of violence he felt

existed at Repton and most of all to the fact that the great majority of

beatings were performed by other boys. “Our lives were quite literally ruled by

fear of the cane,” he wrote.

The white-gloved boazer Carleton, searching his study for the speck of

dust that would justify a thrashing, was typical. In Dahl’s eyes, he was simply

a sadistic thug with a licence to inflict pain. Carleton – actually a boy

called Hugh Middleton – was perhaps the most dreaded of Dahl’s boazers. He was

a “supercilious and obnoxious 17-year-old” with a cane that became an object of

fetishistic interest to the other boys. His “creamy-white monster about four

feet long with bamboo-like ridges all along its length and a round bobble the

size of a golf ball where the handle would have been” struck terror into a

fag’s heart. “Other Boazers used their OTC (Army) swagger-sticks when they beat

the Fags, but not Middleton.”

The beatings were usually performed in the boazer’s study shortly before

going to bed. The victim had a choice: fewer strokes with his dressing gown off

or more with it on. Afterwards, the boy thanked the boazer for his thrashing

before returning to his dormitory, where he would undergo a ritual inspection

of his wounds.

In his book Boy, Tales of Childhood, Dahl describes such

an occasion. The ace cricketer, Jack Mendl, had just beaten him, delivering

four strokes, “so fast it was all over in four seconds”. Now back in the

“bedder”, his fellows insist Roald take down his trousers to show them his

damaged buttocks. Dahl does not dwell on the “excruciating burning pain” he is

suffering. Instead, he recalls the boys’ detailed analysis of Mendl’s

handiwork. “Half a dozen experts would crowd around you and express their

opinions in highly professional language. ‘What a super job.’ ‘He’s got every

single one in the same place!’ ‘Boy, that Williamson’s [Mendl] got a terrific

eye!’ ‘Of course he’s got a terrific eye! Why d’you think he’s a Cricket

Teamer?’”

The scene is comic. At the end, Mendl himself appears in the dormitory,

“to catch a glimpse of my bare bottom and his own handiwork”.

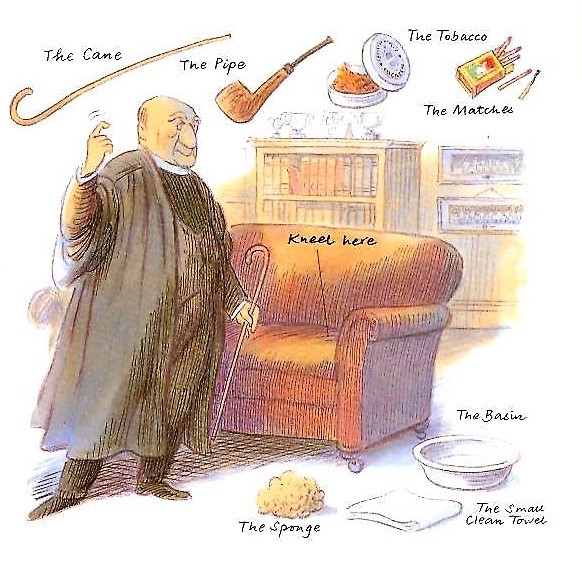

In Boy, Dahl’s memories of that beating surged back with some

ferocity. And this was one incident from the initial draft that he did not

censor. His final account is almost entirely as he first described it. “Michael

was ordered to take down his trousers and kneel on the Headmaster’s sofa with

the top half of his body hanging over one end of the sofa,” he wrote. In

between each “tremendous crack administered upon the trembling buttocks”, the

Boss would light his pipe and “lecture the kneeling boy about sin and

wrongdoing”.

“At the end of it all,” Roald continued, “a basin, a sponge and a small

clean towel were produced by the Headmaster, and the victim was told to wash

away the blood before pulling up his trousers.”

In his mind, it was all the more shocking and hypocritical because the

perpetrator was Geoffrey Fisher, the man who later went on to become Archbishop

of Canterbury. Unfortunately, Roald had made a mistake. Not for the first time,

he sounded off before he had fully checked his facts. For the culprit was not

Fisher at all, but his successor, John Christie. The beating happened in the

summer of 1933, a year after Fisher, as Dahl records in his own letters home,

had left Repton to become Bishop of Chester. More than 50 years later, however,

Dahl blamed the “shoddy, bandy-legged” Fisher for the caning, and painted him

as a sanctimonious hypocrite.

Beatings such as this were unusual. Michael himself was not a small boy,

but an 18-year-old who had abused younger boys.

Extract taken from Storyteller:

The Life of Roald Dahl, by Donald Sturrock (published

by HarperPress, 2010) and reported in Daily

Telegraph, 8 August 2010.

Picture credit: Posy Simonds

For more True Memories, click here

For more items including Prefects, click here

Traditionalschooldiscipline@gmail.com

Comments

Post a Comment