Long, long road to outlawing the cane

In prison, you had to get written permission to punish someone, have a doctor present and give the prisoner a kidney shield. In a school, an 18-year-old prefect could do it. – Jacob Middleton who in 2007 researched why British schools continued to use corporal punishment for so many years.

Corporal punishment in

schools in Britain was abolished by law in 1986 but that decision took a long

time coming.

Twenty years after the

event in March 2007, the Times Educational Supplement (TES) reported on research by Jacob

Middleton, of Birkbeck College, University of London, on the reasons why

schools clung to corporal punishment for so long after many countries had

deemed it inhumane.

He found that as early as

the 19th century, arguments were being made to spare the rod.

AJ Mundella, the Liberal

politician who introduced compulsory education in 1870, declared that “education

should be a privilege, not a punishment”. He was supported by members of the

Humanitarian Society, including George Bernard Shaw.

But while social reformers

theorised, classrooms were fast becoming cauldrons of violence. One teacher was

shot by a 14-year-old pupil. Inspectors were scared to enter classrooms without

a gun.

Then, in the 1890s,

classroom teachers were given legitimate power to punish. Tensions in schools

cooled noticeably. Shortly afterwards, resistance to the cane petered out

entirely – “especially since, with the advent of the First World War,

opposition to violence was seen as unpatriotic, ” the TES reported.

But it resurfaced in the

1930s, when advances in psychology prompted people to discuss the damaging

effects of violence on children. And an academic study revealed that corporal

punishment was less effective than letters home, because it could be concealed

from parents.

By then, the penal system

and the army had already abolished the cane.

The TES reported, ‘“Schools

were out on a limb,” said Mr Middleton. “In prison, you had to get written

permission to punish someone, have a doctor present and give the prisoner a

kidney shield. In a school, an 18-year-old prefect could do it.”’

In 1968 teachers themselves

spoke out against corporal punishment, forming the Society of Teachers Opposed

to Physical Punishment (STOPP). But they met determined opposition from

colleagues. Nigel de Gruchy, then general secretary of the National Association

of Schoolmasters, condemned them as “professional traitors”.

“Unions felt that teachers

were experts,” said Mr Middleton. “Teachers knew how to control children, they

knew what was best for them. Any limit on that was an attack on their

professional status.”

In 1982, two mothers

brought a court case claiming that caning their children against their wishes

infringed their human rights as parents. And so, in 1987, corporal punishment

was banned.

“But the heritage is still

in the education system,” said Mr Middleton.

Corporal punishment had

only been outlawed in state-run schools and it was still lawful until 1999 for

independent (from the state) and “faith” schools to use corporal punishment.

“We've still got working

teachers who could use corporal punishment. Some Christian schools are still

arguing for it as part of their freedom of religious expression. If you ask

teachers, would you like more right to discipline children, many will say yes,”

Mr Middleton said.

“I can't see schools making

a concerted effort to bring corporal punishment back, but nothing is ever

inevitable.”

Corporal punishment remains

unlawful in all British schools.

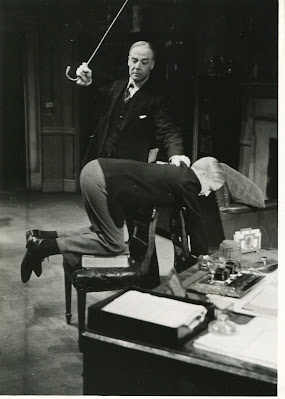

Picture credit:

Dreams of Spanking

Traditionalschooldiscipline@gmail.com

Comments

Post a Comment